Gaynor's News

Judging by the conversations on Twitter, many who watched the first episode of A House through Time on 8 April were outraged at the harsh sentences meted out on the two orphaned boys, Richard Ferguson and Edward Stuart. After all, they’d only stolen two umbrellas from William Stoker’s home at 5 Ravensworth Terrace in Newcastle. Hardly a heinous crime.

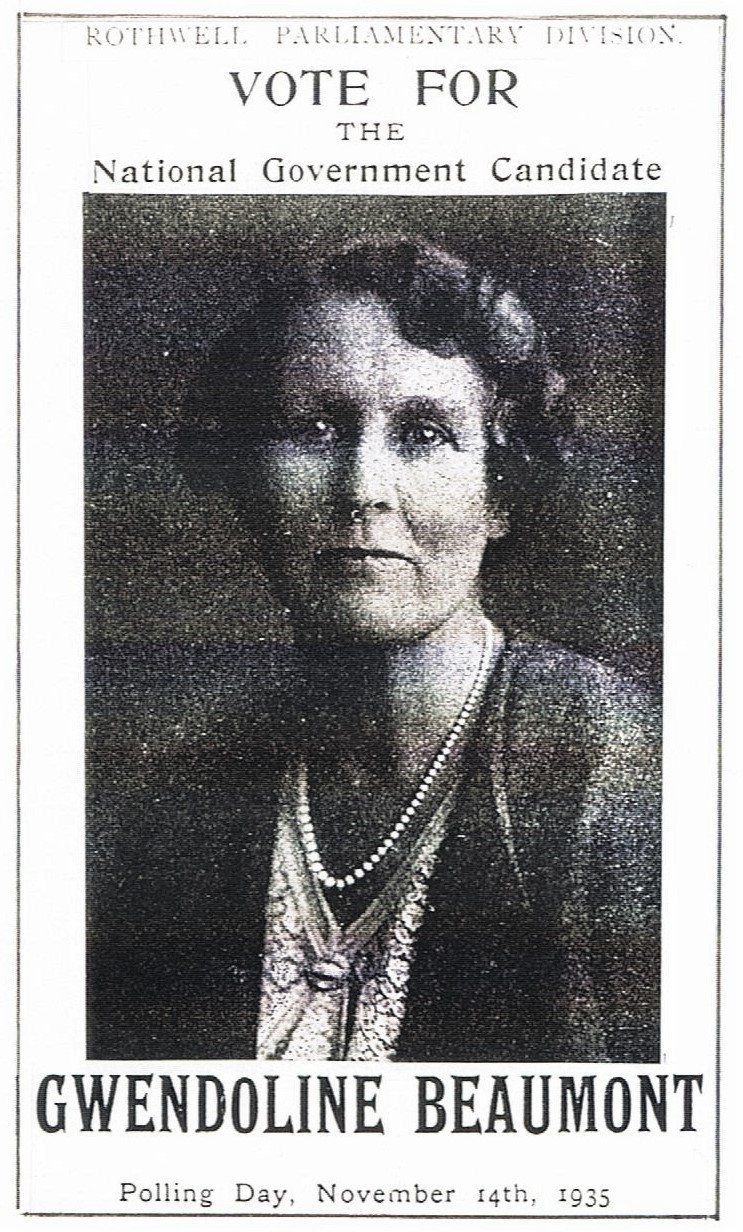

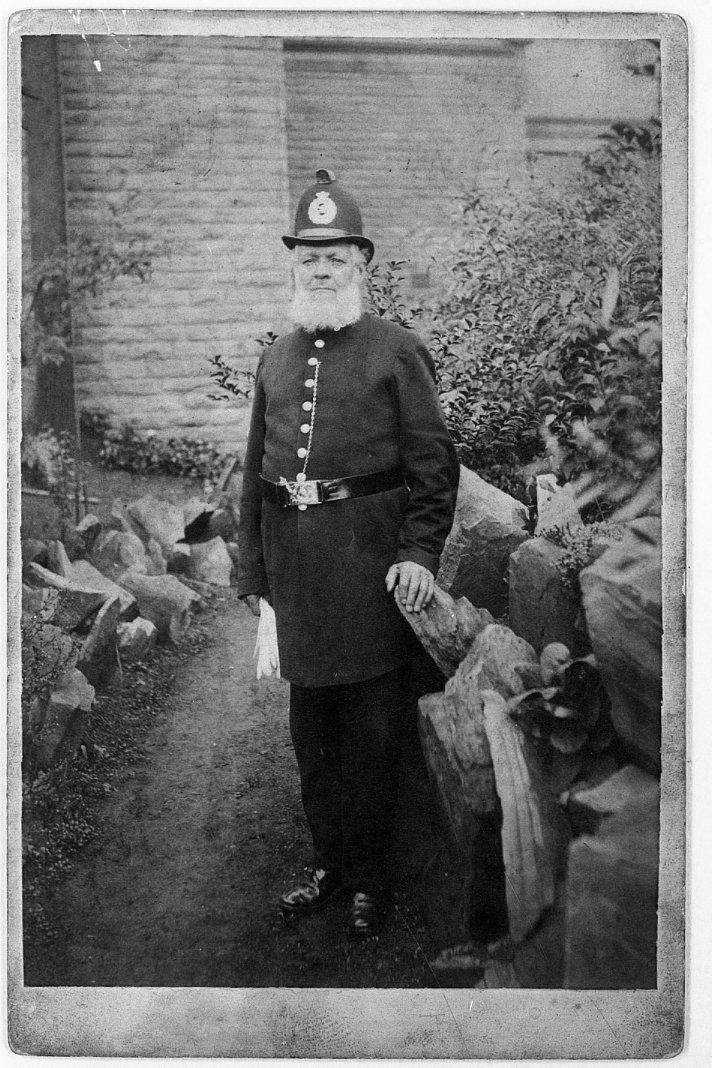

I wonder how my Victorian policeman great great grandfather would have handled the situation. Thomas Bottomley was known for his more gentle style of policing in Manningham, Bradford and I’d like to think he’d have been more lenient – even though the police had to follow strict rules in making sure criminals were brought to justice. He was only once reported for neglect of duty and never for any of the other misdemeanours that other constables were frequently in bother for. Perhaps his neglect of duty was for turning a blind eye to a petty theft by two kids. Perhaps he clipped them round the ear, took the stolen property off them and returned it to its owner. We’ll never know.

But of course, Thomas was a constable in a professional police force. He was guaranteed a wage and worked regular, though long, hours.

In contrast, Newcastle in 1835 had no formal police force. Instead it relied on watchmen to look out for lurking strangers during the night, and unpaid parish constables whose primary duty was to preserve the peace.

Those parish constables were elected annually by parishes and townships. The appointments were compulsory and often unpopular with the incumbents who were usually already following a trade or occupation. As well as a peace-preserving function their roles included numerous and diverse tasks such as collecting county and parish rates, finding transport for military forces, swearing the stocks were in good order and ready for use – and even that people regularly attended church. They had little or no value in crime prevention beyond that of any other able-bodied man, aside from their (often ornately decorated) staff of office. This staff was their only symbol of authority and a useful weapon of self-defence where necessary.

So did parish constables earn any money for their compulsory work?

The parish constables were paid on a sort of piece work basis – in that any monies they did receive in exercising their public duties came through fees and perquisites (perks to you and me) arising from issuing warrants; granting summonses; special attendance at fairs, markets, and sessions; carrying maces; waiting Feasts, and from chance cases of assault and street brawls.

It was a flawed mode of paying men engaged in what was actually time-consuming and often arduous work and it led some parish constables to generate disturbances in order to obtain or extort fees – making them unpopular and devoid of any moral influence on the population. Despite various Police Acts, this type of policing continued in Britain to some degree in a number of districts until the 1856 County & Borough Police Act made having a professional, trained police force compulsory.

It led to some curious goings on, and I particularly liked this tale of Yorkshire-Lancashire rivalry which came to light when a select committee set up by Palmerston, then Home Secretary, to consider the expediency of adopting a more uniform system of police in England, Scotland and Wales, published its report in 1853.

It seemed that Yorkshire police in Todmorden, a town straddling the Yorkshire-Lancashire border, had insinuated that Lancashire constables were going over to Yorkshire for the sole purpose of obtaining cases to bring before the magistrates. Of course, the Yorkshiremen, still working as parish constables, felt they were being robbed of their potential fees and earnings and they complained bitterly. The truth was that properly trained men in the Lancashire constabulary, seeing drunkenness, brawling in public houses and pugilistic fighting, were crossing the invisible county border line to suppress the disorders.

Captain Woodford, chief constable of Lancashire, took action. Ordering his men to only venture over the border when in pursuit of thieves, he declared ‘It is now the business of Yorkshire people to keep order in their own county.’ In consequence, disorders in Yorkshire were left to continue and escalate.

Back to the policing ‘black hole’ of Newcastle

Given the reactive, rather than pro-active, role of the parish constable (especially since he was following his own paid occupation) it would have been up to William Stoker to engage the services of one to help in bringing a prosecution.

Among the witnesses listed on the court indictment sheet and not highlighted in the programme (there’s never space to include everything I guess when there’s so much other exciting information) was another Thomas: Thomas Barkas. He was the local parish constable and we know this as he’s mentioned as such in other local newspaper crime reports of the time.

So it’s likely that he and Stoker worked together to bring the boys to court once William had reported the crime, had the culprits identified by various witnesses and in his role as a lawyer, helped with issuing their arrest warrant. The parish or township which had appointed Constable Barkas would have paid him for this work and it is likely that Stoker also gave him some financial reward. A nice little earner, as they say.

Barkas would also have been responsible (and paid) for keeping Richard and Edward holed up in a lock-up until they came before court, usually the magistrates’ in the first instance. The magistrates would either dismiss the case, refer it to petty sessions or for more serious cases, refer it to the Assizes or Quarter Sessions.

There's no report of this case ever coming before the magistrates’ court, although that doesn’t mean it didn’t. The indictment states the boys were tried for larceny (simple theft), a case that would have usually been heard at the Quarter Sessions, so it is curious that their case was dealt with at the Assizes.

Was it the imminence of the Newcastle Assizes, scheduled for the first week in August 1835 and only held annually in the town that made Stoker push for the trial there? Or was he hoping the crime would be classed as theft from a dwelling house rather than larceny? At the time of the umbrella theft, 31 July 1835, stealing from a dwelling house was a capital crime, meaning it could be punishable by death – although the punishment was more likely to be commuted to transportation.

Of course, Stoker knew the law very well and undoubtedly had influence among other law enforcers of Newcastle. He’d have been familiar with the sort of sentence the boys would receive – it was usual for the times. Although they were ‘just umbrellas’ worth around 5 shillings according to the reports, any theft was an attack on capital and there was no leniency, even for small, light, low-value items.

But was William Stoker any more unkind than his peers?

In the growing urban areas of nineteenth century Britain, the widening chasm between rich and poor often led to the latter looting the former. Through his work, Stoker would have encountered countless examples of petty thieves progressing to career criminals – even Richard may have already been on the slippery slope as he’d already been in court for his involvement in another theft a week or two earlier (although he was acquitted). Naturally, better-off folk were keen to protect their property from what they saw as a ‘feckless underclass’, so did Stoker, with his legal clout, push the umbrella theft case as an opportunity to make an example of these boys, perhaps not only for vengeance but to protect his well-to-do neighbours from similar crimes? Can his actions – even though they point to him just getting these boys off the streets of Newcastle – be thought of more kindly? Might he have believed he was putting Richard and Edward on the right tracks by halting their descent into a life of crime? We’ll never know.

Proper policing in Newcastle

As it was, tackling crime in Newcastle soon came under the watchful eye of a new professional police force. On 2 May 1836, less than a year after the umbrella theft saga, the Newcastle on Tyne City Police was established.

Illustrating the mood of the time, a newspaper report described it thus:

The new police appear a vigorous, well-conducted & intelligent body of men & we learn from several quarters that since they commenced duty the number of skulking vagabonds who have been accustomed on various pretences to annoy respectable inhabitants have materially decreased.’

Clearly, attitudes to those in less fortunate circumstances were not about to improve.

Nineteenth century

newspapers were full of attention-grabbing ‘Murderous Assault on Police’ headlines.

Sometimes these were over-exaggerated, but the murder of police officers engaged in their duties was sadly not uncommon.

Here’s a just a couple of reported brutal incidents in West Yorkshire where two officers lost their lives.

The assault on Police Sergeant Winpenny took place late at night on 23 November, 1895 in Liversedge. Winpenny was attempting to arrest a drunk and disorderly Ruth Colbeck, who had refused to give her name when asked. As Ruth threw herself to the floor, dragging Winpenny with her, biting his finger and screaming ‘murder!’ she attracted a mob of around a hundred or so rough men, who viciously attacked the policeman. Nine men were subsequently arrested at their homes and conveyed to Dewsbury to appear, with Colbeck, before the magistrates. Newpapers described one man, Thomas Albert Heaton, currier, as belonging to one of the best-known families in Liversedge, while the others belonged to ‘the labouring classes’.

Each mob member was charged with inflicting grievous bodily harm on the sergeant. Winpenny was still alive at that time, but as his life was despaired of a dying declaration was taken by the deputy clerk to the court. Four of the men, including Heaton, protested their innocence, but all were remanded in custody for a few days. However only Ruth Colbeck and Benjamin Moorhouse appeared at the January Sessions in Leeds Town Hall, charged on seven counts with assaulting Sergeant Winpenny, obstructing and resisting him in the execution of his duty.

Some witnesses claimed the sergeant had been beside himself with excitement and probably intoxicated, but the chairman told the jury there was no evidence to support these claims. He also added that although death had been caused by a riotous crowd, the two people here were not those accused of that offence. It meant that both Colbeck and Moorhouse were sent to gaol for only a month, even though an assault against the police, whether a blow or a push, was an assault against the law.

Sergeant Winpenny, who died from peritonitis, caused by inflammation & gangrene of the small intestine, 11 days after the attack, was aged 50. He left a widow and eleven children, five of whom were ‘too young to work’. His widow was granted a pension of £15 a year ‘whilst she remained a widow’ and an extra pension of £2 10s 0d a year for each of the youngest five children. The total was less than a third of her husband’s salary. She never remarried.

An entry in the West Riding personnel records for Superintendent Thomas Birkill simply states; 24th November 1887: ‘Murdered. He was deliberately shot at 7.30am & died 3 hours afterwards at Otley, by a poacher named William Taylor who had recently murdered his own child by shooting it for which crime the superintendent was endeavouring to apprehend him .'

The Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer of 25th November 1887, gave a much fuller account of the ‘ reckless brutality and cruel determination that marked the tragedy when the people of Otley were thrown into a state of the wildest excitement by the too true report that a man resident in the town had, in attempting to shoot his wife, taken away the life of his child but ten weeks old, and afterwards, in his defiance of the police to arrest him, shot at and fatally wounded a superintendent of police, Mr Birkill.’

You can read more about this in my book!

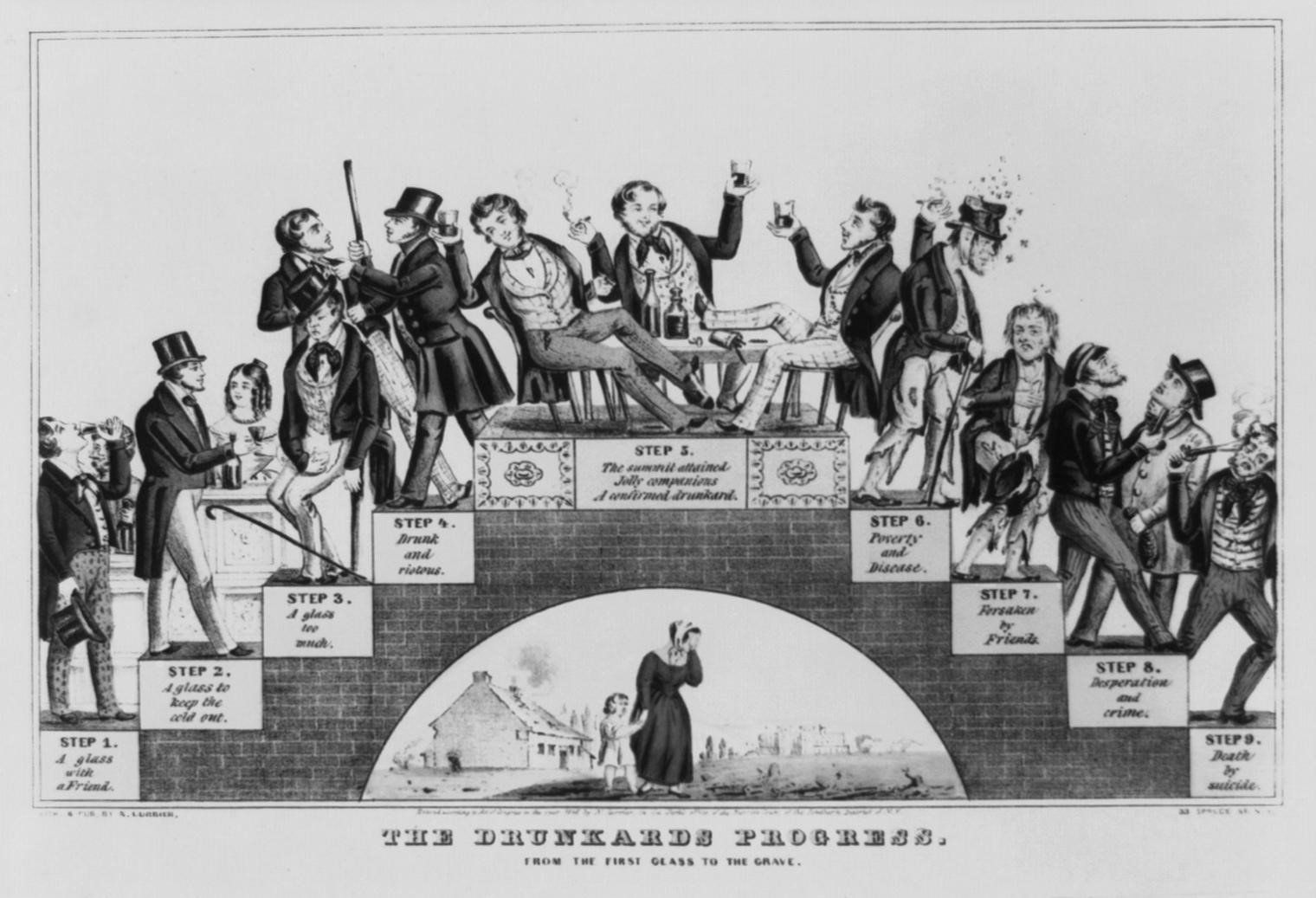

Alcohol consumption posed many

issues for the Victorian police. Not only were the general public succumbing to

liquor’s allure and causing mayhem, but policemen too .

One of the earliest duties of Capt. Edward Willis, Manchester’s new chief constable (after the force was again reorganised in October 1842), was to summon Superintendent Cyrus Alcock to a special meeting of the watch committee on 3rd November 1842.

Alcock was charged with having been frequently in a state of intoxication over the previous two-and-a-half years – other officers had needed to assist him to his home, and there had been stretches of three or four days where he’d failed to attend work. Sometimes he’d been so drunk he couldn’t even sign reports delivered to his home.

After a further three meetings, where further details were presented and discussed, the watch committee decided the evidence wasn’t sufficient to prove his intoxication was a general habit! But he was demoted to police inspector and given chance to prove himself by subsequent better conduct.

This was a slightly different approach to that taken in Bradford. In November 1848, after ten months of dealing with cases of drunkenness within the force, Bradford’s watch committee decided any officer found in a state of intoxication would be dismissed. A directive was added to the instruction book, and a note was ordered to be pinned in ‘a conspicuous place’ in the police office.

As alcohol consumption continued to rise throughout the nation, the situation was so dire that a select committee was appointed in 1877, to look into the problems of intemperance and to introduce a new licensing Bill. One of the findings of the investigation was that although few new public houses had been opened over the previous seven years, there had been a thirty-seven percent increase in the number of beerhouses and off-licences.

This easy access to liquor placed temptation in folk’s way and led to ‘to temptation being fallen into’. People were buying alcohol to consume in their own homes. Sound familiar?

It seems things didn’t improve much in the police forces either.

When Surrey Constabulary revised its constables’ instruction book in 1889, it still found it necessary to state:

" If a member of the force be convicted of drunkenness, he will be liable to immediate dismissal, and the plea that the degree of intoxication was slight, will not be considered as any excuse, or avert the punishment which will inevitably follow this offence."

And in 1899 when Robert Peacock, Manchester’s latest chief constable, delivered his first training lectures, they focused primarily on the licensing laws. He warned against the dangers of taking too much intoxicating liquor, reminding the men that ninety percent of the police who had been dismissed had been sacked because of drunkenness.

As an Observer journalist mused in 1877: ‘A select committee is unlikely to ‘discover the philosopher’s stone, by which a drunken can be at once changed to a sober nation’ .

140 years later, has anything changed much?

Just as today, Victorian policemen were often assaulted while executing their duties.

A correspondent to London’s Evening Standard on the 24th October 1867, questioned why magistrates didn’t impose stronger penalties on those who assaulted the police. Citing a recent case, his view was that 2 months’ hard labour was insufficient punishment for the 3 young ruffians who’d committed a most violent & brutal assault on a constable – asserting that they should have had a few lashes of the ‘cat’. He contrasted the sentence with one given the same week, where a prisoner was sentenced to 18 months’ imprisonment for stealing a few articles of trifling value. If the magistrates did their duty and inflicted the heaviest possible punishment in their power, he said, he would not read of such frequent cases of assaults on the police.

He had a point. Contemporary newspapers were full of graphic accounts of assaults on the police.

150 years ago, in October 1867, the Bury Times reported the ‘outrageous assault on Police-constable Ritchings’ who had been attacked by 2 colliers outside the Hit & Miss beer house in Todmorden at throwing-out time. As the drunken men refused to go home quietly, PC Ritchings drew his truncheon, but it was wrenched from his grasp and used by the men to beat him around the head. As he cried out ‘murder’ the men dispersed and a partly-dressed couple came to his assistance, took him into their house and gave him a cup of tea.

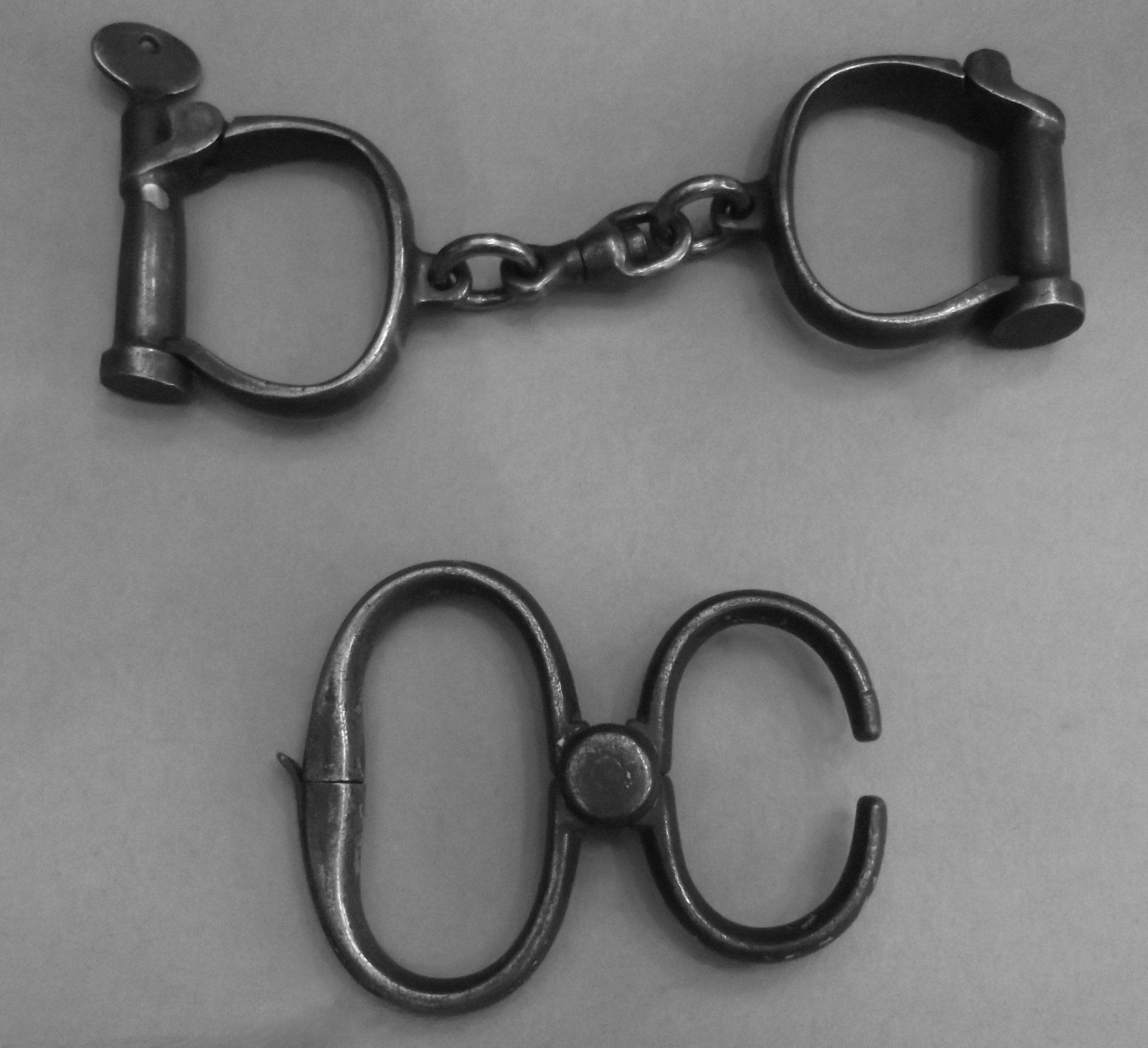

Ritchings’ helmet was later found in a field 25 yards from where the assault took place and the handcuffs nearly buried in mud. Although their lawyer contended that the PC wasn’t that badly injured, the prisoners were committed for trial at the next sessions.

In the same week the Dublin Evening Mail reported a murderous assault on PC Fitzgerald in London.

When a prisoner, who the constable was trying to take into custody for assault on another man, turned, punched the PC violently in the mouth and called out for assistance, a gang of 9 roughs (including a woman) plunged into the affray. One twisted the PC’s arm to breaking point, another tugged his hair and a third kicked him hard at the base of his spine. He was hit in the face by a heavy leather belt and threatened with being shot. Not surprisingly he was totally unfit for duty for some time.

It wasn’t the first time the assailant had been in court. He’d already been convicted of several assaults on the police and private individuals and had recently been released from gaol following a 12-month sentence.

In this case the judge considered the case so serious that he passed a sentence of 5 years’ penal servitude – to deter others from committing such brutal assaults.

On a slightly lighter note, the Bristol Times and Mirror reported that a violent woman, Harriet Railer, a beer house keeper of Langford, had been charged with assaulting the police in the execution of their duty – the duty in question being checking weights and measures. Unhappy that the officer had found several defective measures (presumably she’d been watering the beer), Harriet set about smashing the evidence and hit the policeman across his hand with a copper quart. She threw said quart pot at another PC’s head, causing an incised wound, before taking up a chair to fend off the constables.

She was fined and made to pay expenses for her actions.

Although a police force had been established in the newly created borough of Manchester in June 1839, huge disputes about the legality of levying a rate to pay for it had led to local residents refusing to cough-up.

As a matter of some urgency, a Bill ‘for improving the police in Manchester, adopting the Metropolitan Police Act as a basis for raising a rate to defray the expense of the police’ was put before Parliament and by early October 1839 Colonel Sir Charles Shaw was in his post as Chief Commissioner of the Manchester New Police.

Tasked with putting into force this Act of Parliament by 17th October, the new appointee found instant disfavour with correspondents of the Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser.

The announcement of his appointment had been met with some derision in mid-September.

Beyond the fact he’d been in the service of Don Pedro in Portugal and an officer of the ‘tatterdemalion’ (ragamuffin) British Legion in Spain, his military career was deemed unremarkable. He had written two autobiographical ‘dusty tomes’ but ‘ amongst the egotistical slip slop in which Sir Charles Shaw's history of the astounding events of his busy life abounded’ there was nothing within them to justify his appointment – unless it was simply to drill the ‘bluebottles’ (as the police were disrespectfully alluded to). The correspondent concluded that to be appointed to such a well-paid position, Sir Charles must have had ‘ pressing and peculiar claims upon his patrons’ .

‘With Sir Charles personally we have no quarrel’, he went on, but offered the following advice.

‘Let him steer clear of the Borough Court and its functionaries. The manner in which the business is transacted there, is quite unsatisfactory to the people of Manchester and if he should identify himself with such a blundering, bungling, set of officials, he need not expect the support and approbation of the town.’

A few weeks later, having got something of a scoop, the Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser revelled in printing the strict ‘Rules, Regulations, and Discipline’ that members of ‘ Sir Charles Shaw's Company of Thief-Catchers’ would have to abide by.

In mocking terms it questioned how the common constable’s beggarly pay, without perquisites & subject to deductions at the whim of the chief commissioner, could possibly leave enough money spare to indulge in forbidden drunkenness.

‘A man who is obliged to maintain himself and wife and family, on something less than seventeen shillings per week, and who can afford to get tipsy withal, would be domestic economist worth knowing’ the reporter opined.

Domestic economists they might not have been, but disobedient they were. Even 60 years later the then chief constable of Manchester thought it prudent to remind his men that ' 9/10ths of the men who have been dismissed or called upon to resign have had to leave directly as a consequence of taking too much drink. Let this be a warning to you as, without doubt, indulgence in intoxicating liquor when on duty will in the long run bring ruin both to yourselves and your families.'

Gaynor's News

Judging by the conversations on Twitter, many who watched the first episode of A House through Time on 8 April were outraged at the harsh sentences meted out on the two orphaned boys, Richard Ferguson and Edward Stuart. After all, they’d only stolen two umbrellas from William Stoker’s home at 5 Ravensworth Terrace in Newcastle. Hardly a heinous crime.

I wonder how my Victorian policeman great great grandfather would have handled the situation. Thomas Bottomley was known for his more gentle style of policing in Manningham, Bradford and I’d like to think he’d have been more lenient – even though the police had to follow strict rules in making sure criminals were brought to justice. He was only once reported for neglect of duty and never for any of the other misdemeanours that other constables were frequently in bother for. Perhaps his neglect of duty was for turning a blind eye to a petty theft by two kids. Perhaps he clipped them round the ear, took the stolen property off them and returned it to its owner. We’ll never know.

But of course, Thomas was a constable in a professional police force. He was guaranteed a wage and worked regular, though long, hours.

In contrast, Newcastle in 1835 had no formal police force. Instead it relied on watchmen to look out for lurking strangers during the night, and unpaid parish constables whose primary duty was to preserve the peace.

Those parish constables were elected annually by parishes and townships. The appointments were compulsory and often unpopular with the incumbents who were usually already following a trade or occupation. As well as a peace-preserving function their roles included numerous and diverse tasks such as collecting county and parish rates, finding transport for military forces, swearing the stocks were in good order and ready for use – and even that people regularly attended church. They had little or no value in crime prevention beyond that of any other able-bodied man, aside from their (often ornately decorated) staff of office. This staff was their only symbol of authority and a useful weapon of self-defence where necessary.

So did parish constables earn any money for their compulsory work?

The parish constables were paid on a sort of piece work basis – in that any monies they did receive in exercising their public duties came through fees and perquisites (perks to you and me) arising from issuing warrants; granting summonses; special attendance at fairs, markets, and sessions; carrying maces; waiting Feasts, and from chance cases of assault and street brawls.

It was a flawed mode of paying men engaged in what was actually time-consuming and often arduous work and it led some parish constables to generate disturbances in order to obtain or extort fees – making them unpopular and devoid of any moral influence on the population. Despite various Police Acts, this type of policing continued in Britain to some degree in a number of districts until the 1856 County & Borough Police Act made having a professional, trained police force compulsory.

It led to some curious goings on, and I particularly liked this tale of Yorkshire-Lancashire rivalry which came to light when a select committee set up by Palmerston, then Home Secretary, to consider the expediency of adopting a more uniform system of police in England, Scotland and Wales, published its report in 1853.

It seemed that Yorkshire police in Todmorden, a town straddling the Yorkshire-Lancashire border, had insinuated that Lancashire constables were going over to Yorkshire for the sole purpose of obtaining cases to bring before the magistrates. Of course, the Yorkshiremen, still working as parish constables, felt they were being robbed of their potential fees and earnings and they complained bitterly. The truth was that properly trained men in the Lancashire constabulary, seeing drunkenness, brawling in public houses and pugilistic fighting, were crossing the invisible county border line to suppress the disorders.

Captain Woodford, chief constable of Lancashire, took action. Ordering his men to only venture over the border when in pursuit of thieves, he declared ‘It is now the business of Yorkshire people to keep order in their own county.’ In consequence, disorders in Yorkshire were left to continue and escalate.

Back to the policing ‘black hole’ of Newcastle

Given the reactive, rather than pro-active, role of the parish constable (especially since he was following his own paid occupation) it would have been up to William Stoker to engage the services of one to help in bringing a prosecution.

Among the witnesses listed on the court indictment sheet and not highlighted in the programme (there’s never space to include everything I guess when there’s so much other exciting information) was another Thomas: Thomas Barkas. He was the local parish constable and we know this as he’s mentioned as such in other local newspaper crime reports of the time.

So it’s likely that he and Stoker worked together to bring the boys to court once William had reported the crime, had the culprits identified by various witnesses and in his role as a lawyer, helped with issuing their arrest warrant. The parish or township which had appointed Constable Barkas would have paid him for this work and it is likely that Stoker also gave him some financial reward. A nice little earner, as they say.

Barkas would also have been responsible (and paid) for keeping Richard and Edward holed up in a lock-up until they came before court, usually the magistrates’ in the first instance. The magistrates would either dismiss the case, refer it to petty sessions or for more serious cases, refer it to the Assizes or Quarter Sessions.

There's no report of this case ever coming before the magistrates’ court, although that doesn’t mean it didn’t. The indictment states the boys were tried for larceny (simple theft), a case that would have usually been heard at the Quarter Sessions, so it is curious that their case was dealt with at the Assizes.

Was it the imminence of the Newcastle Assizes, scheduled for the first week in August 1835 and only held annually in the town that made Stoker push for the trial there? Or was he hoping the crime would be classed as theft from a dwelling house rather than larceny? At the time of the umbrella theft, 31 July 1835, stealing from a dwelling house was a capital crime, meaning it could be punishable by death – although the punishment was more likely to be commuted to transportation.

Of course, Stoker knew the law very well and undoubtedly had influence among other law enforcers of Newcastle. He’d have been familiar with the sort of sentence the boys would receive – it was usual for the times. Although they were ‘just umbrellas’ worth around 5 shillings according to the reports, any theft was an attack on capital and there was no leniency, even for small, light, low-value items.

But was William Stoker any more unkind than his peers?

In the growing urban areas of nineteenth century Britain, the widening chasm between rich and poor often led to the latter looting the former. Through his work, Stoker would have encountered countless examples of petty thieves progressing to career criminals – even Richard may have already been on the slippery slope as he’d already been in court for his involvement in another theft a week or two earlier (although he was acquitted). Naturally, better-off folk were keen to protect their property from what they saw as a ‘feckless underclass’, so did Stoker, with his legal clout, push the umbrella theft case as an opportunity to make an example of these boys, perhaps not only for vengeance but to protect his well-to-do neighbours from similar crimes? Can his actions – even though they point to him just getting these boys off the streets of Newcastle – be thought of more kindly? Might he have believed he was putting Richard and Edward on the right tracks by halting their descent into a life of crime? We’ll never know.

Proper policing in Newcastle

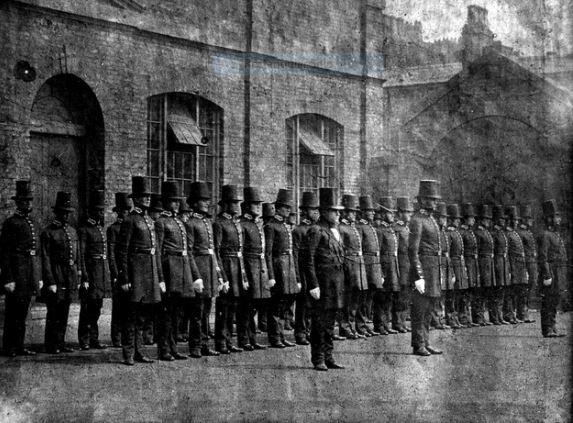

As it was, tackling crime in Newcastle soon came under the watchful eye of a new professional police force. On 2 May 1836, less than a year after the umbrella theft saga, the Newcastle on Tyne City Police was established.

Illustrating the mood of the time, a newspaper report described it thus:

The new police appear a vigorous, well-conducted & intelligent body of men & we learn from several quarters that since they commenced duty the number of skulking vagabonds who have been accustomed on various pretences to annoy respectable inhabitants have materially decreased.’

Clearly, attitudes to those in less fortunate circumstances were not about to improve.